If you don’t find Ed Catmull’s Creativity Inc. difficult, you are not reading it right.

The book is an engaging and easy to read story; however its best lessons are subtle and challenging.

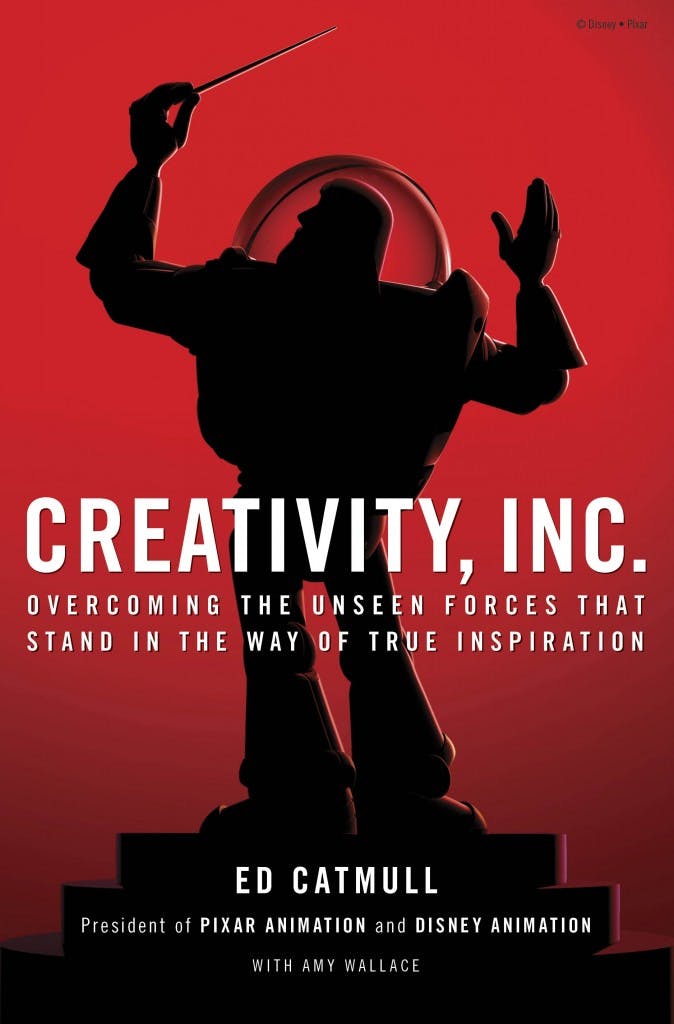

Catmull is co-founder of Pixar, the studio behind Toy Story, A Bug’s Life and Monsters Inc. He has a keen interest in simple, well-informed insights. His thoughtful revelation is that simple well-informed insights often lead you astray.

“Trust the process”

Take his story about setting a price for Pixar hardware in the early days of the company. He sought out the advice of experts and they confidently advised setting a high price since you could always reduce it later. That’s simple, clear advice from people with experience.

However, in this case Pixar’s hardware got stuck with the image “good machines, but too expensive.” Even when they reduced the price, the “too expensive” image did not change. That’s one of the reason’s Pixar didn’t become a hardware company — a happy outcome for all of us it as it turns out, but failure to generate revenue from hardware sales almost sunk the company.

Another lesson comes from their mantra for creative work: “Trust the process.”

In the early days of any creative activity the product is ugly. When writers start to develop a story there are elements that just fall flat. The “Trust the process” mantra reassures the creative team they will get through these difficulties if they just keep at it.

Trusting the process is a useful idea, and yet Catmull observed that when the Toy Story 2 team trusted the process they got deeper and deeper into trouble; well into the production, Catmull had to make the expensive (but ultimately brilliant) decision to go back to the drawing board.

Simple insights can be helpful, but just as often they can lead you astray.

Managing creative teams

Of course, there is a ton of good advice about managing creative teams in Creativity Inc. One tip is about the value of postmortems in capturing the lessons learned after a film has been made.

Catmull warns us that while everyone agrees that postmortems are a good idea, people naturally resist doing them, and may fall into exchanging polite comments rather than raise uncomfortable issues. You need the postmortem process, but more than that you need a mindset that makes sure the process is doing what it is meant to do.

Catmull was trained as a scientist and that perspective shines through the book. Perhaps his biggest contribution to management thinking is his notion of “The Hidden.” That’s the idea that even when we try to be attentive, there will be important issues facing the organization that we will be blind to.

He tells the story of the Toy Story production where, despite leadership’s vigorous efforts to create an open and egalitarian culture the production managers felt they were treated like second class citizens. Leadership had no idea production managers felt this way, even thought– and thesis important — they were looking for exactly this kind of issue.

You have to manage in the knowledge that important issues will always be hidden from you. Catmull says “If you don’t try to uncover what is unseen, and understand its nature, you will be ill-prepared to lead.”

The importance of candor – from everyone

To the extent that Catmull does have a mantra he fully trusts, it is that we need candor from everyone on the team. Big, creative projects require the application of an enormous amount of intelligence, and you can’t access that intelligence unless everyone is contributing.

It is hard to be honest; it can hurt feelings (which is especially a concern if the person with hurt feelings is your boss). Finding ways to engender candor is one of Pixar’s great victories as an organization.

One final fact struck me: At one point, Catmull mentions that he questioned whether he was cut out to be a CEO. All the other CEOs he knew were brash and confident. He, like any good scientist, was full of questions and doubt.

Catmull didn’t fit the standard mold of a leader yet he has proven to be an extremely effective one. So let’s consider this hypothesis: maybe the standard mold is a poor one.

If we in HR continue to hire brash, confident leaders who believe in simple mantras then maybe we are selecting exactly the wrong sort of person to lead in today’s world.