Those of you who are familiar with the radio program A Prairie Home Companion (broadcast on NPR from St. Paul, Minnesota from 1974-2020), will no-doubt be aware of the famous fictional town of Lake Wobegon.

The town exists as the setting for a recurring segment in the program, called “News from Lake Wobegon” – a short monologue of what is happening there – mostly filled with provincial, sometimes touching news.

At the end of each monologue however is this key segment: “That’s the news from Lake Wobegon, where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

A nation of Lake Wobegons

Today – and in homage to Lake Wobegon – psychologists have coined a term called The Lake Wobegon effect. It’s used to describe the tendency to overestimate one’s capabilities [tests show hardly anyone – just 2% – describe themselves as ‘below average’]

The problem is, we now have a nation of Lake Wobegons.

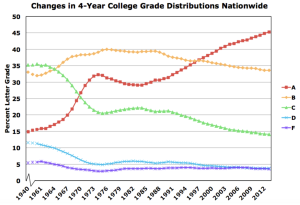

In the early 1960s, just 15% of all college grades nationwide were A’s.

Today, that number has more than tripled, with over 50% of all grades now being A’s.

In fact, the most common grade awarded in colleges nationwide is an A. Some 75% of all the college grades earned by students today are either A’s or B’s.

Source: www.gradeinflation.com

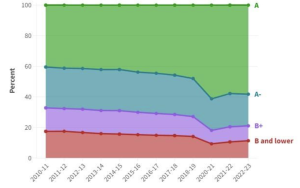

It looks even better at the high-school level. Research by the ACT found that of the 4 million high school seniors who took the ACT test between 2010 and 2021, the number of A-minus students was greater than the number of B-minus students.

This is also reflected in soaring graduation rates. Between 2007 and 2020, the graduation rate at public high schools increased from 74% to 87%.

But the trend of rising Grade Point Averages (or GPAs), doesn’t match scores students get on standardized placement tests like the SAT.

On these tests, the trend has been the opposite, with average scores declining. Results from the other assessments like PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), show that math and reading literacy are flat or down.

It gets more interesting that increases in graduation rates were greatest in high schools with the lowest test scores.

The same pattern is visible in AP (Advanced Placement) classes. AP class grades have risen steadily while AP exam scores have stayed stagnant.

The best (or worst) example of the dichotomy between grades and independent assessments is from the Eagle Academy for Young Men of Harlem, where 94% of students passed their math classes even as 95% of them failed the New York State math assessment.

Grade inflation

The tendency for colleges to inflate grades – that is assigning grades that do not align with content mastery – first started in the 1960s.

Colleges started awarding fewer Ds and Fs when getting failing grades meant becoming eligible for the draft and being sent to the war in Vietnam.

But the trend has accelerated in recent years.

Department of Education rules now require school districts to set annual targets for improvement with possible sanctions for failing to meet them.

As a consequence teachers have devised creative ways of raising grades, such as by allowing students to retake exams, removing penalties for late assignments, and adjusting grading scales.

A common example is the increasing use of online credit-recovery classes.

These are online remedial courses delivered that students can take if they fail a class, rather than attending summer school or being forced to repeat a grade.

It’s estimated that about 70% of all high schools in America use them. Some have more than half of their students enrolled in credit-recovery programs.

Dumb and Dumber

The rational reaction to this situation would be to tighten standards and disincentivize giving grades that exaggerate the level of knowledge a student has achieved.

But the opposite is happening. In fact school administrators have responded by lowering standards even more.

When New Jersey considered raising testing standards last year, they were opposed because higher standards would be “unfair” to black and Latino students in urban districts.

The San Diego Unified School District now allows students to hand in work late, redo poorly graded assignments indefinitely, and even cheat without receiving a lower grade as a penalty.

The justification for this is that over 20% of black and Hispanic students receive D or F grades while only 7% of white and Asian students do so.

Oregon dropped its graduation exam because the education department concluded the test produced inequitable outcomes for minority groups.

A race to the bottom

Letter grade distribution at Yale, 2010-2023

So how’s this all working out?

One analysis found that after schools implemented new grading scales which led to more As and fewer Fs, students with low test scores attended class less often and put in less effort.

The attendance of high-scoring students, meanwhile, did not change.

Such policies also contribute to wider gaps in GPAs and standardized test scores between high- and low-achieving students.

The latter group tends to include more minority students.

So efforts to help students that do poorly are actually harming them.

It should be noted that grade inflation is most common in the humanities.

STEM fields have done a better job of maintaining standards. Less than 65% of grades in economics, mathematics and chemistry are A’s, compared to more than 80% of grades in the humanities.

So grade inflation disincentivizes students from majoring in the sciences and mathematics.

As education has become less intellectually rigorous, bachelor’s degrees have become less content-driven.

A consequence of this is that universities raise their grades to distinguish their graduates artificially in a world where the bachelor’s degree has increasingly become the new high-school diploma.

Harvard has a 3.8 average GPA, up from 3.6 a decade ago.

It was 2.7 in 1963.

Maybe the university relocated from Boston to Lake Wobegon.

While this grade inflation may boost job-placement statistics in the short term, it’s an intellectual race to the bottom.