I invested 38 years in the corporate world and my experience spanned a myriad of departments – to include human resources where I oversaw our leadership development program and played a critical role in personnel policy and practice. My time in HR was particularly rewarding because it came on the heels of a series of people management assignments. The chance to study how truly great leaders recognized and rewarded top talent – and then contrast their approach with the masses – was revealing, particularly as regards performance evaluations and end-of-year reviews.

Perhaps more important, I was able to better appreciate the role of the employee in making certain the performance discussion was truly an engaging discourse – not a “check the box” exercise administered by a manager when the fiscal year ground to a close. Time and again I watched otherwise assertive and ambitious employees meekly sit through a performance discussion – nod at the appropriate time and then return to their job with little to no value offered them – and minimal substantive feedback.

I asked myself why?

Many times it was a failure of the manager – and on multiple levels. Sometimes that involved a lack of training for the supervisor, ambiguity on the employee job responsibilities, or simply a general reluctance to offer quality feedback. The insights gained helped inform our leadership training.

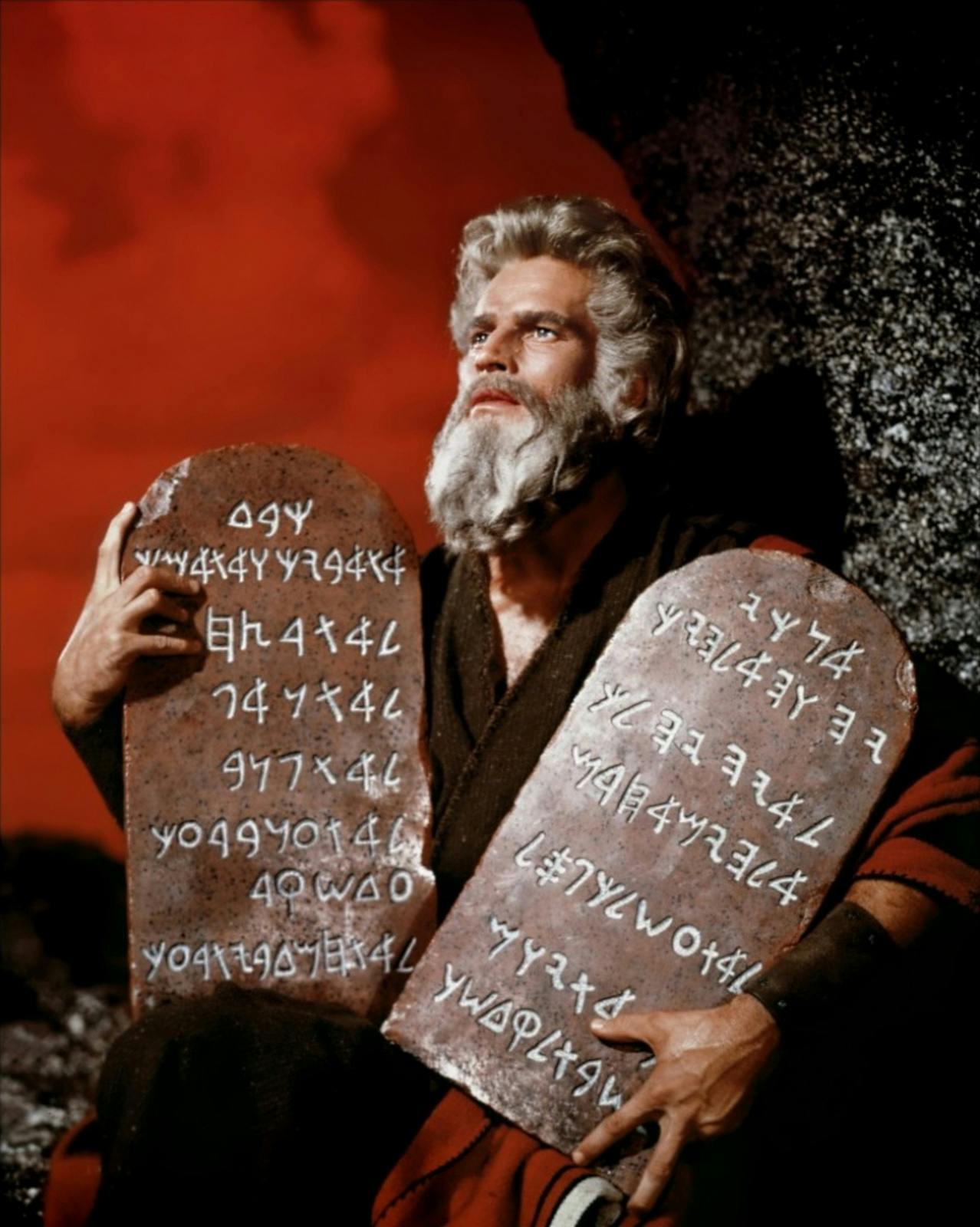

But I was equally impressed by the lack of ownership from the employee/worker – an almost passive submission to “the process.” I invested time trying to find viable ways to change that. The summary of those learning’s ultimately became what I was to call “The Performance Review Ten Commandments” – something of a manifesto I used to challenge all employees to take ownership in their career and job assessments.

The Commandments eventually became a part of my book, The Compass Solution: A Guide to Winning Your Career. That book is essentially a leader’s guide to optimizing your job experience – and represents the lessons of a lifetime in one of the most turbulent industries in the world – pharmaceuticals.

I’ve used The Commandments to educate employees in a variety of career fields – but always with a focus on their obligations – not just their supervisor of record. I believe it offers practical insights for all – to include the traditional human resources generalist.

Here then, is the chapter entitled “Every Time You Sit Down” from the book.

Every Time You Sit Down

“It is never too late to be what you might have been.” – George Eliot

Performance evaluations.

Some in the corporate world argue they are the bane of true performance enhancement. Formal, systematized, and driven at times by human resource departments more concerned with company approved guidelines deemed legally defensible than in truly differentiating top talent and motivating employees to perform.

A fair and equitable performance evaluation process is not easy to build or to administer. Some years ago I was fortunate enough to develop a system for one of our legacy companies that was used for over a half-dozen years. I can safely say I learned that no matter how much time and attention is devoted to its creation, there is no perfect approach to assessing people’s skills and overall contributions.

But there are a couple of outputs that resonated for me. Again – tips from a corporate survivor you might consider. And those tips begin with one very simple notion.

Your performance review is not something done to you. It’s something you should be prepared to lead through.

Here’s a list of inalienable rights and responsibilities you should consider if you are going to maximize your contributions – and yes, the individual performance reviews to come. The Corporate Survivor Performance Review Ten Commandments:

1. Thou shalt make certain you know the expectations for your job.

Sounds stupid, doesn’t it? That should be fairly intuitive. Don’t kid yourself; your interpretation of what your role is and your manager’s will likely be different, sometimes radically different. It’s been my experience that there is usually a lot of misinterpretation. You can’t afford that. Sit down and discuss what is expected. Ask questions. Make sure you have a clear vision of what great looks like. The number one reason people fail – they don’t know what it is they are supposed to do. And the other reasons are far behind.

2. Thou shalt make sure you understand how you will be trained.

And if your answers to the bulleted point above don’t align with the training that will be provided, ask how the gaps will be addressed. Companies are sometimes very clear in saying what they expect, but much more ambiguous in providing the hands-on training needed to help you do the job. Without the training you are being set up for failure.

3. Thou shalt take ownership in soliciting and in receiving feedback and do it as early and as often as possible.

Challenge your manager to offer it even if they are uncomfortable in providing it. It’s your career. You either drive it or you are a passive reactor. Take the steering wheel.

4. Thou shalt ask for as many examples of excellence as you can handle – either through your manager or via your peers.

It’s hard to demonstrate outstanding performance if you don’t know what it looks like to begin with.

5. Thou shalt take notes when the subject of performance arises.

Too many people fly by the seat of their pants. Don’t be one of them.

6. Thou shalt determine your performance evaluation is something you can heavily influence if you choose.

But to do that requires your taking an active role in your own development. Unfortunately most are passive recipients. Wrong approach. Every formal meeting with your manager/supervisor/leader should include some degree of discussion around how you’re tracking on performance. Someone told me once, “Every time you sit down, you should know where you stand.” Pretty sage advice.

7. Thou shalt call out early on that you expect to be a top performer.

Engage your manager in that undertaking. Challenge them (and yes, you will hear that term repeatedly when we talk about performance evaluations) to help you get there. Let them know you hold them just as accountable for an outstanding review as they hold you. Bold? Yes, but I will guarantee you those few who set the bar high for themselves and do the same thing with their managers set a tone that will serve them well later.

8. Thou shalt document your successes.

Make that a dynamic record that you can, at a moment’s notice, provide to your manager. Use it to populate the self-assessment portion of your mid- and end-of-year review. The alternative is Creative Writing 101 — the mindless search to justify your greatness and to meet the time line for your review.

9. Thou shalt never pass on the opportunity to comment in writing on your review.

That electronic summary is a legal document. It can dictate your next promotion, your salary increase, and yes, your job security. It is a lot more than a simple letter. Treat it as such.

10. Thou shalt retain every performance review you receive and plan to reference those documents as a potential free agent for the rest of your professional life.

Again – no proof of performance equals no performance in the eyes of a prospective employer.

Rules for Leaders

And if you’re in a formal leadership position, a couple of things to consider as you assess the people who report to you:

- Spend the time to do it right. I’ve seen far too many managers who gloss over the process or attach a number rating and then move on after a half hour of completing a spreadsheet. I’ve even read performance reviews that were basically generic with slight tweaks for everyone on the team. That’s an insult to your people.

- Differentiate your talent. The greatest single step you can take toward company mediocrity is when you group everyone in the middle. Top performers will see it, they will resent it, and the very best will not tolerate it.

- Be specific and be behaviorally based in your comments. No one cares about your feelings nor do they want to hear generalities around their personality traits. If you can’t offer a specific example you can’t provide quality feedback.

- Avoid the inherent biases that can afflict leaders. We tend to reward persons with similar backgrounds, belief systems, and approaches to the job. A major mistake.

Whether you are a follower or a supervisor – every time you sit down you should know where you stand.