Accenture’s 2014 College Graduate Employment Survey compares the expectations and perceptions of 2014’s university graduates with the realities of the working world according to both 2012 and 2013 graduates.

This comparison casts a focused and specific lens on the issue of entry-level talent development, and, gives us some insightful data.

Accenture’s survey underlines that, at the end of the day, many organizations are not effectively developing their entry-level talent.

When we consider that 69 percent of 2014 graduates state that more training or post-graduate education will be necessary for them to get their desired job, we see that organizations are likely facing a major talent supply problem.

Grads expect on-the-job training, but few get it

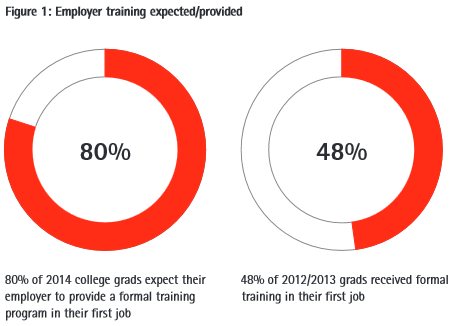

New graduates and entry-level talent’s perceive that their organizations will provide them with career development training: 80 percent of 2014 grads expect that their employer will provide the kind of formal training programs necessary for them to advance their careers.

Despite this, the percentage of graduates that actually receive such training is low, creating a significant discrepancy between expectation and reality.

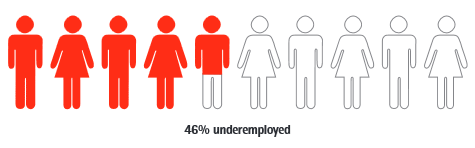

Half of new graduates are underemployed

Another concern when it comes to recent college graduates is that 46 percent (nearly half) of 2012/2013 graduates working today report that they are significantly underemployed (i.e. their jobs do not really depend on their college degrees). This statistic was at only 41 percent a year ago.

Accenture’s survey found that 84 percent of 2014 graduates believe they will find employment in their chosen field post graduation, and 61 percent expect that job to be full-time. But again, we find a stark contrast between expectation and reality.

Just 46 percent of 2012/2013 grads reporting holding a full-time job – and 13 percent have been unemployed since graduation.

How long do recent graduates stay at the jobs they do have? More than half (56 percent) of 2012/2013/2014 graduates have already left their first job or expect to be gone within one or two years. Is this be a reflection on the lack of development for entry-level talent? It seems more than plausible…

Paltry pay doesn’t meet expectations

Recent graduates are also finding discrepancies between expectations and realities when it comes to income and job prospects.

Of the 13 percent of 2012/2013 grads who have been unemployed since graduation, 41 percent believe their job prospects would have been enhanced had they chosen a different major (and, 72 percent expect to go back to school within the next five years).

Among Accenture’s 2014 survey respondents:

- 43 percent expect to earn more than $40,000 per year at their first job;

- However, just a minimal 21 percent of the 2012/2013 graduates who are in the workforce are actually earning at that level.

- 26 percent of these graduates report making less that $19,000, a troubling figure when you consider that roughly 28 percent of 2014’s graduates will finish school with debt of more than $30,000.

A better focus on market relevancy

The Accenture’s study does have some silver linings, however.

- Increasingly, college students are turning an eye towards what they can do to be more market relevant. Some 75 percent of those who graduated this year took into account the availability of jobs in their field before selecting their major, compared to 70 percent of 2013 graduates and 65 percent of those in the class of 2012.

- Another positive: 72 percent of 2014 graduates agree/strongly agree that their education prepared them for a career (compared to 66 percent of 2012/2013 grads), and 78 percent feel passionately about their area of study.

- Plus, 63 percent of 2014 graduates felt that their university was effective in helping them find employment opportunities, an increase from 51 percent among their recently graduated peers.

- Recent graduates are also increasing their chances of employment by being geographically flexible, and 74 percent of 2014 graduates said they would be willing to relocate to another state to find work, and 40 percent of those would be willing to move 1,000 miles or more to land a job.

Is the C-Suite even thinking of entry-level talent?

Accenture’s study does, however, put into question many of the highly publicized reports that point to human capital/talent acquisition issues as the No. 1 concern in the C-Suite.

If talent is the No. 1 issue, where is the attention to entry-level talent? Is the attention being placed exclusively on development for upper-level positions?

It’s clear that there are multiple factors influencing graduates’ struggles for acceptable employment, including the rise of part-time and contingent work, but training and development is an important part of any entry-level position. The survey points to six areas in which organizations can focus on to help meet talent supply challenges:

- Reassess hiring and retention strategies;

- Hire based on potential, not just immediate qualifications;

- Use talent development as a hiring differentiator;

- Remember that tangibles matter, even to Millennials;

- Cast the net more widely; and,

- Use talent development and other benefits as part of a total rewards and attraction approach.

Just a lot of lip service?

These are logical conclusions. But, perhaps the biggest logical conclusion is that organizations are just paying lip service to the so-called war for talent and aren’t convinced that the there is, in fact, an actual shortage of talent out there.

Am I wrong?

This originally appeared on China Gorman’s blog at ChinaGorman.com.