Five years after the iPhone was introduced, companies are still struggling with how to handle after-hours usage by their employees.

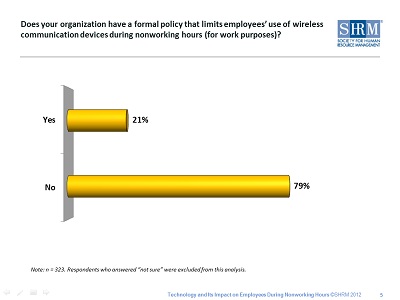

New research from SHRM, the Society for Human Resource Management, says more than half the companies responding to a survey about usage policies don’t have any.

“Employers are not creating policies that delve into employees working outside of the traditional workday,” said Evren Esen, manager of SHRM’s Survey Research Center. “Whether an employee responds to e-mail at night or during the weekend is usually linked to organizational norms. If there is such an expectation, then employees are likely to follow suit.”

Potential overtime claims

Only 21 percent of the 323 respondents said they had a written policy governing after-hours work on wireless devices. Another 26 percent had some sort of informal policy, which gets communicated to the staff by managers and supervisors, word of mouth, or in other ways.

Those informal policies tend to apply more to personally-owned equipment; 69 percent of the respondents with some informal policy apply them only to employee-owned devices. Written policies tend to apply only to company-provided equipment by 53 percent to 47 percent, SHRM found.

However, it doesn’t really matter, from a legal standpoint, who owns the equipment. As any employment lawyer will tell you, if the work is being done at the behest of the employer — explicitly or otherwise — you’re facing the potential for an overtime claim.

However, it doesn’t really matter, from a legal standpoint, who owns the equipment. As any employment lawyer will tell you, if the work is being done at the behest of the employer — explicitly or otherwise — you’re facing the potential for an overtime claim.

Last year, when I discussed the growing number of cases being brought under the Fair Labor Standards Act for OT in connection with after-hours wireless use, attorney Todd Fredrickson, managing partner in the Denver office of labor firm Fisher & Phillips, said he’s telling his client, “If you don’t want to pay for it, don’t let it happen.”

Sending and responding to emails and texts after work hours is practically part of the job description these days for exempt workers. (Your exempts are all correctly classified, right?) The cases that have come up, almost all involve hourly workers.

Class action lawsuit in Chicago

The occasional email is unlikely to prompt a suit. Frederickson’s rule-of-thumb guidance is if takes less than five minutes, it’s de minimus, meaning such a minor interruption of off-hours as to not be compensable. But when there are regularly multiple of these interruptions, things gets dicey.

That’s what happened in Chicago where the police department issued BlackBerrys to police sergeants a few years back. Sgt. Jeffrey Allen got so many work emails while off work he brought a class action suit for overtime.

Warns employment specialist Christopher J. Harristhal,

The extensive use of PDAs has only recently been receiving attention in the courts and few decisions have yet been rendered. The trend will undoubtedly continue, however, and employees and plaintiff’s lawyers will become more savvy about how to exploit these practices and leverage their claims for wages and overtime.”

That puts those companies who leave the decision up to their employees in an almost indefensible position should an FLSA claim be raised. How many leave it up the employee? SHRM found most of them without any policy do. Overall, that means almost 41 percent of all the respondents leave it up to the workers to decide how much work to do after hours.

A formal policy for smartphones and PDAs

You can guess what the lawyers would tell you. Write a policy governing the use of wireless devices for work related matters during off hours.And make sure it’s communicated.

Explains Harristhal:

Those policies should, for example, admonish employees to record all hours worked, direct that they not use company email or PDAs for after hours work, remind employees of the company’s overtime policies and need for authorization before performing overtime work and closely monitor telecommuting by nonexempt employees.

But like the advice doctors dispense about getting more exercise and eating better, it doesn’t appear likely too many companies will be taking Harristhal’s advice. SHRM found on 9 percent said it was very likely they adopting a policy of some kind in the next three years; 62 percent said it was not likely.

Besides lawsuits and big payouts, there’s another reason to adopt a policy: For 27 percent of SHRM’s respondents who have a policy, there’s a life/work balance issue involved.