It’s your first day at work, and you are excited to meet your new colleagues — a little nervous, but hopeful, that the work and culture of your new company will inspire you to do great things. After your onboarding meetings, you get a box of newly minted business cards, and they look like this:

It’s your first day at work, and you are excited to meet your new colleagues — a little nervous, but hopeful, that the work and culture of your new company will inspire you to do great things. After your onboarding meetings, you get a box of newly minted business cards, and they look like this:

What kind of company would make your salary visible to everyone? Why would they risk stirring the stew of complex emotions that comes with sharing your salary?

In the winter of 2016, my company, Truss, made our salaries transparent internally. How did we do it? By building an infrastructure first — process, communication, and tools to insure that our efforts built trust, reduced risk, scales with size, and sustains over time with minimal administrative overhead.

Start with why

We’re all aware that women and underrepresented minorities are still paid less than white men for the same work. This is true even for well-intentioned companies because there are several systemic, fundamental biases that preserve and even amplify inequality in compensation.

I and my co-founders, Mark Ferlatte (CTO) and Jennifer Leech (COO), were determined not to follow that default path with our diverse company, so we started researching initiatives that could be a foundation for our growing firm. There were several companies, notably Buffer, that had made salaries transparent to great effect, but it was still a rare program across companies.

In addition, we didn’t find any companies that made salaries transparent explicitly to remove bias in compensation. For Truss, anchoring on the “The Why” was a crucial step early in the process, and helped us to stay focused on the outcome and engaging Trussels (our employee nickname) to join in achieving it.

The “Compensation Programs & Practices Survey,” conducted by World at Work, found that broad pay transparency remains uncommon.

But here’s the rub: If you aren’t considering making salaries transparent, your employees might be doing it without you. A few years ago Google employees created a spreadsheet and began self-reporting their salary As recently as this September, it was revealed that over 200 Microsoft employees had created their own salary database to enable better negotiations.

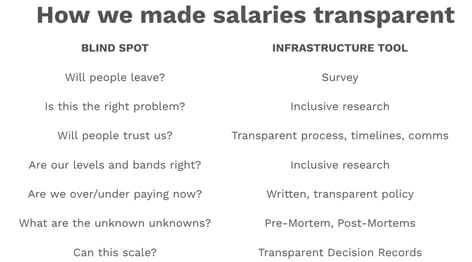

Address high-risk blind spots

Because salary and compensation can be a sensitive topic for employees, and bias is a complex problem, we used our experience from building complex software systems and applied an “infrastructure-first” approach. That is, in order to make salaries transparent means addressing the interaction between systems of people, software, and operations — the infrastructure — to be successful. At this early stage, we identified our blind spots with the highest risk first, and created tools that addressed those blind spots in a systematic and predictable way.

Blind spot 1: Will people leave?

In March of 2016, the first step was to survey our 20 employees to assess interest in (or resistance to) the project. Only one person indicated hesitation, and over 50% were highly positive about making salaries transparent, so we felt confident that we addressed this basic, but essential risk.

Blind spot 2: Is this the right problem?

As a company, we moved to the edge of our knowledge, researching root causes of salary disparity in negotiation, leave policies, hostile environments and individual visibility and recognition, among many other factors. We had already built some infrastructure to measure demographics because, as our friends from Project Include pointed out, you can’t manage what you can’t measure. Crucially, the research team included people at different levels of the company, including their perspective at this early stage.

Blind spot 3: Will people trust us?

We knew that a transparent communication channel was a critical piece of infrastructure if we were to reduce the risk that comes with low employee engagement. We dedicated several retro meetings to get input, concerns, fears and opportunities from the entire company. From these, we clarified our rollout plan and set a series of dates to announce our findings.

Blind spot 4: Are our levels and bands correct?

The next step was to bring employees with different levels of experience into the ongoing legal, financial, levelling and banding research. This was the largest part of the workload. First, we had the challenging task of finding available, reliable compensation data that wasn’t prohibitively expensive to obtain. Second, we realized we had to create a levelling schema from scratch (oops!) that would scale and incorporate future roles. For anyone attempting to create salary transparency, this will be your biggest lift. It is absolutely worth it — having reliable data, and a regular cadence for reviewing, adjusting, and refining it will build ongoing employee trust.

Blind spot 5: Are we overpaying or underpaying?

Once we had levels, we learned that some of our corresponding compensation bands were off, some too low and some too high. We made two critical decisions. First, if we were overpaying someone for their level that was the mistake of the leadership team. We will not adjust anyone’s salary downward. Second, for people who were being underpaid, we established a timeline where each employee was bumped up within one quarter. That enabled us to maintain cash reserves while assuring — and delivering — on the promise to increase salaries.

Blind spot 6: What are the unknown unknowns?

While we could predict different risks and blind spots, there’s always the unforeseen and unplanned. To address this, we made sure to conduct pre-mortems and retros with the entire team. These were incredibly valuable ways to include different perspectives, build trust by addressing challenging questions, and occasionally experience the “I never thought of that!” insight that moved the project forward.

What happened

Following more than nine months of work, we announced that salaries were transparent and where to find the data, and the reaction was ho-hum. Of course there was curiosity, adjustments and additional areas where we could — and would — improve. However, because we set up an infrastructure of consistent communication, hit our deadlines and engaged employees in creating the solution, there wasn’t much that was new. Mostly, there was satisfaction in taking a bold step to ensure that everyone, regardless of race or gender, was being paid equally for the same level and performance.

In the last two years, Truss has nearly quadrupled in size to around 80 people, and so far the tools, processes and infrastructure for salary transparency have been able to scale. We added periodic internal surveys, quarterly reviews of salary, leveling and banding. We developed playbooks for hiring, recruiting, onboarding, reviewing and compensation that are available to every employee, so that we understand the process, our roles and can contribute improvements.

In addition, we’ve implemented Truss Decision Records (TDR), a practice we’ve borrowed from great software documentation practices. In each TDR, we publish the problem we’re addressing, alternatives we considered, potential risks and the final decisions we made. Anyone in the company can access TDRs to understand “The Why” or to suggest an improvement. In total, these processes and tools represents a scalable, repeatable, sustainable infrastructure for making salaries transparent.

This can scale

Finally, “How can we make salaries transparent when we’re a company of 10,000 people?”

This is a common question we’ve heard from executives at other companies. They are bewildered by how to implement salary transparency when there is a long history involving orders of magnitude more employees. It is undoubtedly more challenging, but in conversation with two execs that have already initiated the process at larger companies, the core sequence holds — with three points of emphasis:

- First, it is more incumbent on leaders to be clear about “The Why,” and communicating it well. This is the cornerstone for gaining trust.

- Second, take a page out of modern software development and start with a pilot and iterate. Pick an autonomous business unit or a geographic region and run through the process. Some companies are trying the method of only revealing salaries under the senior or executive level. The data is still out there, but I think this approach risks reducing trust, because it opens execs to the question of whether they are hiding something. This is a missed opportunity for leadership to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with their employees.

- Finally, setting leveling and salary bands will be a bigger effort, and the company will likely find some embarrassing outliers. In this case, it’s better to take the initiative to correct any mistakes than to have employees discover this on their own.

Postscript: Unexpected benefits

There are some unexpected benefits of salary transparency that tangibly improved our business in other areas. For example, our internal data show that the faster we move a prospect through the hiring pipeline, the higher probability they will accept our offer. Making salaries transparent reduces our overhead in recruiting, hiring and onboarding because everyone is working from the same data, and because negotiations are far more limited. This speeds up our application-to-signing system, which in turn has a direct impact on our ability to hire great people.

An even more unexpected benefit is in sales and business development. Anyone in the company can build a staffing model with explicit revenue, cost and profit expectations for project proposals because the data is transparent and accessible. The impact is that we can be faster to respond to prospects and existing customer requests. Again, our data show this has a direct correlation with closing new deals.

Key takeaways

- Be clear on your “Why” — Establish purpose first with your key stakeholders.

- Reduce risk by using an infrastructure-first approach — Adopt tools, processes and communications so that your effort builds trust, reduces risk, and engages employees at all levels

- Do your research, especially on salary band and levelling data. Assume it will take longer than you think, but it is worth it.

- Leverage salary data to reduce overhead — especially in hiring — and to accelerate other activities.